Download Accelerator - Async Rust Edition

Breaking news! Here’s a blog post about async Rust, and it’s not a philosophical debate1! Today we’re going down the rabbit hole of download accelerators, though of course that’s just an excuse to explore a living async Rust program. After all, I spent last 12 months writing quite some async code, so I thought I’d give back and share a taste of its exotic flavor. If you have been reluctant to try async because of a negative sentiment on the internet, I hope this post may trigger your curiosity. Bon appétit!

Background

For the impatient: you can jump to the second half of this post that dives into the technical details, or you can even go straight to the code.

Still here? Glad to see at least one person decided to read on! The subsections below provide some background before moving on to the implementation bits: what is a download accelerator? How is that related to async programming? Is any of this relevant for “real-world software development” ™?

Here we go.

1. On download accelerators

Download accelerators were quite popular back in the good old days, when most websites offered low bandwidth per connection. As you can imagine, downloading big files was slow, so people started looking for a creative workaround. It was a matter of time till someone came up with a smart and effective idea: if the server throttles bandwidth per HTTP connection… why not start multiple connections at the same time, letting each of them retrieve a chunk2 of the file in parallel?

To illustrate the point, consider the case in which you have internet access with a download speed of 1 MiB/s. If you were to download a file from a website that throttled bandwidth at 200 KiB/s per connection, then your download speed would normally cap at 200 KiB/s (leaving the remaining 800 KiB/s unused). If, instead of a single connection, you used 5 connections and downloaded the file’s chunks in parallel, that’d get you to a download speed of 1MiB/s, which is 5x faster! Isn’t that neat?

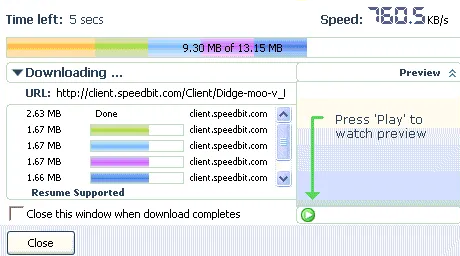

For the picture lovers out there, the screenshot below shows an in-progress parallel download, as displayed by the venerable Download Accelerator Plus. Note how each chunk download is rendered in a different color. You can almost feel the speed!

2. Concurrent downloads and async Rust

Do you see where this is heading? If we want to write a download accelerator in Rust, we need a mechanism to concurrently download file chunks, wait for all the downloads to finish and afterwards join the resulting blobs together into a single file. All of this is made possible by the hero of legend: async Rust!

“Heresy!”, you might reply. “What about good old multi-threaded programming? Where I come from, we’d start a thread for each chunk and download the chunk’s bytes using normal a.k.a. synchronous IO. Keep your async kool-aid and leave us in peace!”

Hmm… That criticism resonates with me! Async enthusiasts like to point out the overhead that comes with threads3, but given the choice I’d still default to threads most of the time. Do we have the choice, though? As of today, the majority of the Rust ecosystem has in fact embraced async, making it the path of least resistance for most IO related code. Many libraries out there don’t support synchronous IO at all, exposing only an async API! Given this state of affairs, I’d rather set my preferences aside in favor of convention. I’m too pragmatic to die on this hill4.

3. The real world

Having decided to go with async Rust, instead of swimming against the current, now let’s consider how programming a download accelerator relates to real-world projects.

The explanation is, fortunately, short. This very blog post was in fact triggered by a problem I recently faced at work: I was uploading files to Amazon S3 and was surprised by the low throughput I was getting5. Their own documentation suggested to split the file in chunks and upload each chunk in parallel. In other words, I had to program… an upload accelerator! Your mileage may vary, as they say, but in my case I saw speedups of 5x to 8x6. Not bad!

As you can see, a bit of async knowledge pays off in practice. It’s not just a circus trick to pretend you are a 10x engineer or to pass a leetcode interview.

The program

Phew! I thought we’d never get to this part of the post… Thanks for bearing with me for so long. And now for the last leg of the race.

1. Run it!

Our download accelerator is little more than a toy program, so the best way to introduce it is through its minimal interface. Here’s how you can run it:

git clone https://github.com/aochagavia/toy-download-accelerator.git

cd toy-download-accelerator

cargo run --release -- https://pub-7d144d0f220f4a61890f3eb37a9a103f.r2.dev/random-big 25

The last line compiles7 and runs the program using cargo (Rust’s package manager). Everything after the -- will be passed to the program as command line arguments. In this case, we are passing the url we want to download from (a 250 MiB file full of random bytes8) and the size of the chunks (in MiB).

If you don’t want to run some random dude’s code on your computer (a very wise precaution), here’s what the output looks like:

$ cargo run --release -- https://pub-7d144d0f220f4a61890f3eb37a9a103f.r2.dev/random-big 25

Downloading `https://pub-7d144d0f220f4a61890f3eb37a9a103f.r2.dev/random-big` using up to 6 concurrent requests and 25 MiB chunks...

The file is 250.00 MiB big and will be downloaded in 10 chunks...

* Chunk 0 downloaded in 1447 ms (size = 25.00 MiB; throughput = 17.27 MiB/s)

* Chunk 1 downloaded in 1594 ms (size = 25.00 MiB; throughput = 15.68 MiB/s)

* <rest of the chunks omitted for brevity>

File downloaded in 6822 ms (size = 250.00 MiB; throughput = 36.64 MiB/s)

Checksum: 1c7ca01f009b2776c4f93b2ebded63bd86364919b4a3f7080a978a218f7d2c55

The program downloads the file in-memory, calculates its SHA256 checksum and prints it to the screen. If you see the same checksum I got above, that means the chunks were correctly assembled on your side (yay!). By the way, we are not saving the file to disk, because this is a toy program anyway and you probably don’t want me messing with your filesystem9.

2. Does it really improve download speed?

That depends on the bandwidth you have available, but you can easily test it yourself. You just need to download the whole file in a single request and check whether there is a meaningful throughput difference.

Remember the command line argument that specifies the size of the chunks? We previously set it to 25 MiB, but you can also set it to a higher value like 999 MiB. This will result in a single chunk because it exceeds our file’s size. Here’s what the output looks like on my machine:

$ cargo run --release -- https://pub-7d144d0f220f4a61890f3eb37a9a103f.r2.dev/random-big 999

Downloading `https://pub-7d144d0f220f4a61890f3eb37a9a103f.r2.dev/random-big` using up to 6 concurrent requests and 999 MiB chunks...

The file is 250.00 MiB big and will be downloaded in 1 chunks...

* Chunk 0 downloaded in 9233 ms (size = 250.00 MiB; throughput = 27.08 MiB/s)

File downloaded in 9470 ms (size = 250.00 MiB; throughput = 26.40 MiB/s)

Checksum: 1c7ca01f009b2776c4f93b2ebded63bd86364919b4a3f7080a978a218f7d2c55

There are a few things that catch my attention:

- In the single-request scenario, shown above, the final throughput (26.40 MiB/s) is a bit lower than the chunk’s throughput (27.08 MiB/s). That’s because, before starting the chunk download, we send a HEAD request that is taking some time and brings down the average speed.

- The parallel download (from the previous subsection) achieved a final throughput of 36.64 MiB/s, which is clearly better than 26.40 MiB/s.

If you aren’t convinced yet, try running the code on a machine with a fast internet connection. That’s where things get really interesting! Fortunately, I have a cheap VPS on Hetzner, so I ran the measurements there out of curiosity. The speedup was considerable: the single-request download averaged about ~35 MiB/s, whereas the parallel download got me ~135 MiB/s. Sweet!

3. Show me the code!

The full code is available on the project’s GitHub repository, but here’s a heavily commented copy of the function that coordinates parallel downloads. The context above and the inline comments should set you on the right track, though some parts might still be hard to understand. Feel free to clone the repository, load it in your IDE, and go down the rabbit hole!

// Send GET requests in parallel to download the file at the specified url

//

// Important: we haven't implemented a mechanism to detect whether the file

// changed between chunk downloads (e.g. do both chunks belong to the same

// version of the file?)... so don't just copy and paste this in a production

// system :)

async fn get_in_parallel(

// The HTTP client, used to send the download requests

http_client: &reqwest::Client,

// The URL of the file we want to download

url: &str,

// A unique reference to a byte slice in memory where the file's bytes will be stored

buffer: &mut BytesMut,

// The desired chunk size

chunk_size: usize,

) -> anyhow::Result<()> {

// Each chunk download gets its own task, which we will track in this `Vec`.

// By keeping track of the tasks we can join them later, before returning

// from this function.

let mut download_tasks = Vec::new();

// The semaphore lets us keep the number of parallel requests within the

// limit below. See the type's documentation for details

// (https://docs.rs/tokio/1.37.0/tokio/sync/struct.Semaphore.html)

let semaphore = Arc::new(Semaphore::new(CONCURRENT_REQUEST_LIMIT));

// After the last chunk is split off, the buffer will be empty, and we will

// exit the loop (see the loop's body to understand how we are manipulating

// the `buffer`).

while !buffer.is_empty() {

// The last chunk might be smaller than the requested chunk size, so

// let's cap it

let this_chunk_size = chunk_size.min(buffer.len());

// Split off the slice corresponding to this chunk. It will no longer be

// accessible through the original `buffer`, which will now have its

// start right after the end of the chunk.

let mut buffer_slice_for_chunk = buffer.split_to(this_chunk_size);

// Each download task needs its own copy of the semaphore, the http

// client and the url. Without this, you'd get ownership and lifetime

// errors, which can be puzzling at times

let chunk_semaphore = semaphore.clone();

let chunk_http_client = http_client.clone();

let url = url.to_string();

// Get the chunk number, for reporting when the download is finished

let chunk_number = download_tasks.len();

// Now spawn the chunk download!

let task = tokio::spawn(async move {

// Wait until the semaphore lets us pass (i.e. there's room for a

// download within the concurrency limit)

let _permit = chunk_semaphore.acquire().await?;

// Get the chunk using an HTTP range request and store the response

// body in the buffer slice we just obtained

let start = Instant::now();

let range_start = chunk_number * chunk_size;

get_range(

&chunk_http_client,

&url,

&mut buffer_slice_for_chunk,

range_start as u64,

)

.await?;

// Report that we are finished

let duration = start.elapsed();

let chunk_size_mb = buffer_slice_for_chunk.len() as f64 / 1024.0 / 1024.0;

println!("* Chunk {chunk_number} downloaded in {} ms (size = {:.2} MiB; throughput = {:.2} MiB/s)", duration.as_millis(), chunk_size_mb, chunk_size_mb / duration.as_secs_f64());

// Give the buffer slice back, so it can be retrieved when the task

// is awaited

Ok::<_, anyhow::Error>(buffer_slice_for_chunk)

});

// Keep track of the task, so we can await it and get its buffer slice

// back

download_tasks.push(task);

}

// Wait for the tasks to complete and stitch the buffer slices back together

// into a single buffer. Since the slices actually belong together, no

// copying is necessary!

for task in download_tasks {

// The output of the task is the buffer slice that it used

let buffer_slice = task

.await

// Tokio will catch panics for us and other kinds of errors,

// wrapping the task's return value in a result

.context("tokio task unexpectedly crashed")?

// After extracting tokio's result, we get the original return value

// of the task, which is also a result! Hence the second question

// mark operator

.context("chunk download failed")?;

// This puts the split-off slice back into the original buffer

buffer.unsplit(buffer_slice);

}

Ok(())

}

4. So what?

For a long time I was reluctant to let async Rust enter my code, but at some point I had to compromise out of pragmatism. It took some getting used to, but I’m currently of the opinion that async is an elegant extension to the language, in spite of its rough edges and the criticism you’ll often hear on the internet.

I should probably write a follow-up article comparing this implementation of the download accelerator against a synchronous one, showing that the differences between them are not that great. It will take some time, though, so I’m hoping today’s article already shows that async Rust is nothing to be afraid of (as you could otherwise believe if you spend too much time reading blog posts 😅). So… maybe you should give it a try next time you have a chance!

5. Bonus: call for contributions

The current implementation of the download accelerator is pretty barebones. I’d be open to pull requests implementing a more user-friendly user interface, be it a TUI (e.g. using ratatui) or a GUI (not sure what library is worth using there). If you are interested, go ahead and open an issue on GitHub so we can discuss (or just send me an email).

A word of thanks

Though I’m no expert in programming language design, I think the novelty of Rust’s approach makes async a really hard nut to crack. I remember using non-blocking IO in Rust before we had async / await and it was painful to say the least. Having async / await be part of the language is in my eyes a huge step forward! Hats off to all the people who made it happen, and thanks for driving Rust and its ecosystem further (even when the work itself sometimes gets you more flak than praise).

Special thanks to Jon Gjengset, who’s Decrusting the tokio crate was crucial to let the pieces of the puzzle fall in their place. He’s an excellent teacher, so if you are trying to get a better grip on the Rust ecosystem, definitely have a look at his stuff (and, if you find it useful and can afford it, consider sponsoring him).

Finally, thanks to Bart, Jouke, Orhun and Tim, who read an early draft of this blog post. Any remaining errors are of course their fault my own.

-

Async Rust is somewhat controversial, with strong opinions in favor and against it. If you’d rather dive into the “async debate”, a must read is Without Boats’ blog. ↩︎

-

HTTP Range Requests allow you to GET a specific range of bytes, instead of the whole response in one go. They have been available since HTTP/1.1. ↩︎

-

Switching between threads on a single CPU incurs overhead (see this Wikipedia entry for details). The more threads you add, the more time is spent just switching between threads, rather than doing actual work! This is a big issue in some scenarios, like the so-called C10K problem (in fact, the C10K problem is the prime example where non-blocking IO on a few threads is “the solution” ™, because otherwise the context switching overhead makes everything grind to a halt). However, in many applications the number of threads stays reasonably low and you shouldn’t see decreased performance using synchronous IO. That’s why I say that I prefer to use threads when I have the choice (my rule of thumb is to only start worrying when having more than 100 threads, but take that with a grain of salt). ↩︎

-

There are crates out there implemented on top of synchronous IO (instead of async), but they are usually less popular and the chance is high that you’ll still have to use async due to other dependencies. My experience is that you might as well bite the bullet early on. “If you can’t beat them, join them”, I guess… ↩︎

-

Upload speed was in the order of 25 MiB/s, which is slow for a server, especially when it’s in the same AWS region as your S3 bucket. ↩︎

-

I’d expect the speedup to be negligible when uploading from a slow connection (what most of us have at home), but I didn’t measure it. However, I did measure the effect parallel uploads had on my server, which is in the same AWS region as the S3 bucket: performance skyrocketed to between 125 and 200 MiB/s. ↩︎

-

You’ll have to gather your patience and wait for it to compile, because the project unfortunately has lots of dependencies. That’s one of Rust’s strengths and weaknesses, as this blog post explains in more detail. ↩︎

-

Hosted on Cloudflare’s R2, of course, to avoid getting a surprise bill if this post goes viral! ↩︎

-

If you are looking for a real-world download manager written in Rust, I recently saw one pass by on the Rust subreddit. It’s open source, but I haven’t looked into it. Try it at your own risk! ↩︎